Bambusa vulgaris (PROTA)

Introduction |

| General importance | |

| Geographic coverage Africa | |

| Geographic coverage World | |

| Vegetable | |

| Medicinal | |

| Timber | |

| Fuel | |

| Ornamental | |

| Forage / feed | |

| Auxiliary plant | |

| Fibre | |

| Food security | |

| Climate change | |

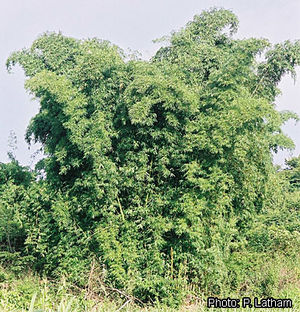

Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex J.C.Wendl.

- Protologue: Coll. pl. 2(2): 26, t. 47 (1810).

- Family: Poaceae (Gramineae)

- Chromosome number: 2n = 72

Vernacular names

- Common bamboo (En).

- Bambou, bambou de Chine (Fr).

- Bambu vulgar (Po).

- Mwanzi, mwazi (Sw).

Origin and geographic distribution

Bambusa vulgaris originated in the Old World, probably in tropical Asia. It is only known from cultivation, although escaped and naturalized populations exist. Common bamboo is the most widely grown bamboo throughout the tropics and subtropics. In tropical Africa it is widely grown and also occurs subspontaneously.

Uses

The stems are used for construction and fencing, but also for tool handles, furniture, handicrafts, stakes, pots, weapons, irrigation pipes and bows for fishing nets. In Kumasi (Ghana) the stems are used in construction as temporary support material. A more recent development in Ghana is that bamboo stems are used for flooring, panelling and furniture. In Tanzania the stems serve as poles to support banana plants and they are used as distillation pipes for liquor making. Split stems are made into baskets, fences, roofs and roof tiles. The stems are also used as fuel. They provide good quality pulp and are used for paper making, e.g. in India. The young shoots are edible. In Rodrigues (Mauritius) a decoction of the growing point of the plant mixed with roots of Job’s tears (Coix lacryma-jobi L.) gives a refreshing drink. The leaves are browsed by goats. Stem sheaths are used as covers for beehives. Bambusa vulgaris is planted for erosion control and as an ornamental. In Sierra Leone it is planted to mark boundaries. In Nigeria a drink of macerated leaves is taken against venereal diseases. In DR Congo the leaves form part of preparations used for treatment of measles.

Production and international trade

The worldwide production and trade of Bambusa vulgaris products is considerable, but no statistics are available.

Properties

For both green-stem and yellow-stem cultivars the density of the stem wall is about 0.63 g/cm³ at 12% moisture content. Shrinkage from green to 11.3% moisture content is 9.7–14.0% radial and 6.0–11.9% tangential. For green-stem cultivars at 17% moisture content, the modulus of rupture is 84 N/mm², compression parallel to grain 25 N/mm² and shear 7 N/mm². For yellow-stem cultivars at 16% moisture contents the modulus of rupture is 86 N/mm², compression parallel to grain 32 N/mm² and shear 4 N/mm².

The working and machining properties of the stems are poor. The stems are not straight, not easy to split, and inflexible, but they are thick-walled and initially strong.

Among bamboos, the carbohydrate (starch and sugar) content of the stems mainly determines the susceptibility to insects and fungi. As Bambusa vulgaris has a high starch content, it is more easily attacked than other bamboo species, such as Dendrocalamus giganteus Wall. ex Munro. The stems are very susceptible to attack by powder-post beetles. Preservation to protect against these beetles and other biological degradation is of vital importance for long-term service. The inner and outer walls of bamboo stems are rather resistant to penetration by preservative liquids, and the uptake is mainly restricted to the ends of the stems.

Stem fibres from Bambusa vulgaris from tropical Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Gabon and Congo) were on average 2.6–2.9 mm long, with a diameter of 17.1–20.0 μm and a lumen diameter of 3.5–7.3 μm. The average chemical composition was: cellulose 41–44%, pentosans 21–23%, lignin 26–28%, ash 1.7–1.9%, silica 0.6–0.7%. The solubility in hot water was 3–5%, in alcohol-benzene 2–3%, in 1% NaOH 20–22%. Papermaking studies have shown that pulp obtained from the stems of Bambusa vulgaris has an exceptional tear strength, comparable to that of pulps made from softwoods. It could be used as a substitute for softwood pulp and for flexible packaging paper grades, either alone or in blends with other fibre sources. Bambusa vulgaris can also be successfully used as a raw material for particle board manufacture.

Young shoots are whitish pink in colour and tender, and they have a fair canning quality. The approximate chemical composition of young shoots per 100 g edible portion for green-stem and yellow-stem cultivars respectively is: water 90 g and 88 g, protein 2.6 g and 1.8 g, fat 4.1 g and 7.2 g, carbohydrates 0.4 g and 0 g, fibre 1.1 g and 1.2 g, Ca 22.8 mg and 28.6 mg, P 37 mg and 27.5 mg, Fe 1.1 mg and 1.4 mg, ascorbic acid 3.1 mg and 0 mg.

Ingestion of large amounts of leaves has been recorded to cause neurological disorders in horses, but this was not related to poisoning by hydrocyanic acid. A chloroform extract of the leaves is active against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The presence in the plant of taxiphyllin, a cyanogenic glucoside, has been reported. Stigmasterol has been isolated from Arthrobacter globiformis fermented shoot.

Description

- Bamboo with a short, thick rhizome and not closely tufted stems; stem (culm) erect, sinuous or slightly zig-zag, up to 20 m tall, up to 12 cm in diameter, hollow, wall (3–)7–16(–20) mm thick, glossy green, yellow, or yellow with green stripes, internodes 20–45 cm long, with appressed dark hairs and white waxy when young, becoming glabrous, smooth and shiny with age, nodes oblique, slightly swollen, basal ones covered with aerial roots; young shoots dark brown to yellow-green.

- Leaves alternate, simple; stem leaves with sheath more or less broadly triangular, 15–45 cm × 17–35 cm, covered with appressed black or brown hairs, auricles 2, 0.5–2 cm long, with pale brown bristles 3–8 mm long along the edges, ligule 3–8 mm long, slightly toothed, blade broadly triangular, 4–15 cm × 5–10 cm; branch leaves with sheath 6–10 cm long, hairy outside, auricles rounded, 0.5–1.5 mm long, with a few bristles 1–3 mm long, ligule 0.5–1.5 mm long, blade linear-lanceolate, 6–30 cm × 1–5 cm, base rounded, apex acuminate, margin scabrous, glabrous.

- Inflorescence a large panicle 2–3 m long, on leafless branches, bearing small groups of spikelets at the nodes.

- Spikelets 12–20(–35) mm × 3–6 mm, laterally flattened, comprising 1–2 glumes, 4–12 florets and a terminal vestigial floret, glumes ovate, acute, lemma ovate, 9–11 mm long, 11–15-veined, palea as long as lemma, 2-keeled, 6-veined; florets with 6 exserted stamens, 3 unequal lodicules, ovary narrowly oblong, style long, thin, hairy, terminating in 2–3 stigmas.

- Fruit not developing.

Other botanical information

Bambusa comprises 120 species indigenous to Asia and the Americas. Bambusa vulgaris is the most easily recognized species of all known bamboos. In a young stem, the primary branches are prominent; they are borne alternately along the stem, together forming a gigantic fan-like structure which is conspicuous from some distance. The variability within Bambusa vulgaris is great and a thorough study of the worldwide variation is necessary. Classification of the different forms should preferably be done at cultivar level (cultivar groups, cultivars). At least three groupings of cultivars can be distinguished:

- Plants with green stems.

- Plants with yellow stems (‘golden bamboo’), often with green stripes of different intensity. Usually the stems have thicker walls than those of the green stem group. This group is often distinguished as Bambusa striata Lodd. ex Lindl.

- Plants with stems up to about 3 m tall, 1–3 cm in diameter, green, with 4–10 cm long inflated internodes in the lower part (‘Buddha's belly bamboo’). This group is often distinguished as Bambusa wamin Brandis ex E.G.Camus.

Bambusa bambos

Bambusa bambos (L.) Voss (spiny bamboo; synonym: Bambusa arundinacea (Retz.) Willd.) is native to India to southern China, and cultivated throughout the tropics, including Ghana and Kenya. It has stems up to 30(–40) m tall with a diameter up to 18 cm. In Ghana the stems are used for construction. In South-East Asia they are important raw material for the paper making industry.

Growth and development

Bambusa vulgaris clumps expand rapidly during the first 5–6 years (from 0.5 m diameter in the first year to 4.5 m in the 6th year) and slower thereafter (to 7 m diameter after 10 years). Young shoots grow rapidly. In 2 weeks they can develop into stems 3–4 m tall, reaching 20 m in length in 3 months. Stems reach maximum diameters after 9 years. The number of young shoots per clump that develop into full-grown stems increases on average from 1.6 in the first year to a maximum of 5.3 in the 4th year and decreases to 2.5–3.5 from the 9th year onward. On average, a mature clump produces 3–4 new stems per year and bears 30–90 stems. In the Niari valley in Congo (average annual temperature 25.5°C, average annual rainfall around 1000 mm), 4.5-year-old Bambusa vulgaris planted at a spacing of 6 m × 6 m, with surviving density of 226 plants/ha, on average had 31 stems per clump and 7000 stems per ha. Flowering is uncommon in Bambusa vulgaris. When a stem flowers, it produces a large number of flowers, but no fruits. Low pollen viability due to irregular meiosis seems to be one of the reasons for the absence of fruiting. Eventually the stem dies, but the clump usually survives.

Ecology

Bambusa vulgaris grows best at lower altitudes; above 1000 m altitude stems become smaller in length and diameter. It thrives under a wide range of moisture and soil conditions, growing in almost permanently humid conditions along rivers and lakes, but also in areas with a severe dry season, where the plants may become completely defoliated. It is frost hardy down to –3°C.

Propagation and planting

Bambusa vulgaris is easy to propagate vegetatively, by clump division, by rhizome, stem and branch cuttings, by layering and by tissue culture. Rhizome cuttings (offsets) give good results when taken from 1–2-year-old stems, but cutting damages the mother clump and rhizome cuttings are not convenient for large-scale plantations. The easiest and most practised propagation method is by stem or branch cuttings. In the Philippines best results have been obtained with one-node cuttings from the lower parts of 6-month-old stems, planted horizontally in moist soil at about 20 cm depth. Treating cuttings with a 100 ppm solution of the growth hormone indole butyric acid improved results. Planting is recommended during the late rainy season and at a spacing of 6–12 m × 6–12 m. In Côte d’Ivoire 2-node cuttings are recommended, planted obliquely in the soil with the upper part emerging. The easy vegetative propagation of Bambusa vulgaris explains its often apparently wild occurrence: clumps may establish from pieces of stems used for poles, fences, props, stakes and posts set on river banks for mooring boats.

Successful in-vitro regeneration procedures for Bambusa vulgaris have been developed using nodal segments or buds on Murashige and Skoog medium.

Management

Weeding is recommended in the first 2–3 years after planting, 2–3 times per year, preferably during the rainy season. Irrigation and fertilizer application considerably improve growth and yield. Protection from animals is important, because they readily browse the young shoots. The plants should also be protected from fire. Where Bambusa vulgaris is planted at close spacings to compensate for young plants dying, the first thinning is carried out at an age of 5–6 years, and the final density is established at 12–13 years age. In Tanzania management of planted Bambusa vulgaris mainly consists of clearing the ground around the clumps.

Diseases and pests

Diseases of Bambusa vulgaris include leaf blight (Cercospora sp.), basal culm rot (Fusarium sp.), culm sheath rot (Glomerella cingulata), leaf rust (Kweilingia divina, synonym: Dasturella divina) and leaf spots (Dactylaria sp. and Glomerella cingulata). A serious disease in Bangladesh is bamboo blight caused by Sarocladium oryzae, killing affected clumps within 3–4 years. Bamboo blight especially occurs on sites with impeded drainage. It can be controlled by cultural practices such as removal of infected stems and burning of debris, and by fungicides.

Harvested stems are very vulnerable to attack of powder-post beetles (Dinoderus spp.). Termite damage can be serious, especially of harvested stems in contact with the ground.

Harvesting

Harvesting normally starts 3 years after planting. Full production is reached 6–8 years after planting. Selective cutting of stems 2-year-old or older is recommended. In tropical Africa it has been recommended to selectively harvest one half to two-thirds of the adult stems on a clump every 3–4 years. Young shoots for consumption should be harvested in the first week of their emergence.

Yield

Yields recorded for tropical Africa are 10 t dry weight per ha per year for Côte d’Ivoire and 15 t for Congo. In trials in Congo, yields were higher for Bambusa vulgaris than for Oxytenanthera abyssinica (A.Rich.) Munro. For the Philippines the annual yield per ha is estimated at 2250 stems or 20 t dry weight. The dry weight ratio for stem, branches and leaves is about 70%, 22% and 8% respectively. The ratio of paperpulp/stem production is about 1:3.

Handling after harvest

Post-harvest treatment of the stem should aim at reduction of the moisture and starch content to increase its durability. Traditionally, harvested stems of Bambusa vulgaris are immersed in running or muddy water for about 3 months. In this process, the starch content is reduced, mainly by bacterial degradation. However, the susceptibility to insects and fungi is normally hardly reduced. Other traditional practices are painting with slaked lime, which reduces water absorption and makes the surface become alkaline, thus delaying fungal attack, and plastering of bamboo mats with a thick layer of mud, clay or sand mixed with lime or cement, which keeps the mats protected against rain and prevents the entry of insects. For safe and long-term use, however, traditional methods do not suffice and chemical preservation is necessary. For preservation, boron salts dissolved in water are most commonly used. Often, the stems are simply treated by placing their base in a container with a preservative; complete submersion of stems is also practised.

Young shoots should be consumed or prepared immediately after harvesting because they become inedible within some hours if left untreated.

Genetic resources

Bambusa vulgaris is represented in most botanical gardens in the tropics. Because of the wide variability of this bamboo, extensive, worldwide germplasm collection is recommended.

Prospects

Because of its easy propagation, rapid growth, long life, high yield and wide applicability, Bambusa vulgaris has good prospects as an alternative for wood in tropical Africa. Drawbacks, however, are the limited durability and poor working properties of the stem material. Structural use is not recommended without preservation to protect the stem material against insects and fungi. Bambusa vulgaris has good prospects for the production of pulp and biomass for energy.

Major references

- Burkill, H.M., 1994. The useful plants of West Tropical Africa. 2nd Edition. Volume 2, Families E–I. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, United Kingdom. 636 pp.

- Chihongo, A.W., Kishimbo, S.I., Kachwele, M.D. & Ngaga, Y.M., 2000. Bamboo production-to consumption systems in Tanzania. [Internet] INBARs Bamboo and Rattan Development Programmes. http://www.in ar.int/publication/txt/ INBAR_Working_Paper_No28.htm. May 2007.

- Chilufya, H. & Tengnäs, B., 1996. Agroforestry extension manual for northern Zambia. Regional Soil Conservation Unit, Nairobi, Kenya. 120 + 124 pp.

- CTFT (Centre Technique Forestier Tropical), 1962. Bambous en Afrique (Arundinaria alpina, Bambusa vulgaris, Oxytenanthera abyssinica). Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 85: 24–32.

- Dah-Dovonon, J., 2001. Recherches pour la promotion et le développement du bambou et du rotin dans le Sud-Bénin. In: Agbo, B.P., Arodokoun, D.Y., Aïhou, K. & Matthess, A. (Editors). Recherche agricole pour le développement. Actes de l’atelier scientifique 1, Niaouli, 11–22 janvier 2001. Programme Régional Sud-Centre du Bénin. pp. 270–285.

- Doat, J., 1967. Les bambous, source éventuelle de cellulose pour l’Afrique. Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 113: 41–59.

- Dransfield, S. & Widjaja, E.A., 1995. Bambusa vulgaris Schrader ex Wendland. In: Dransfield, S. & Widjaja, E.A. (Editors). Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 7. Bamboos. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, Netherlands. pp. 74–78.

- Groulez, J., 1966. Plantations de bambous dans la vallée du Niari (Congo-Brazzaville). Bois et Forêts des Tropiques 110: 13–31.

- Liese, W., 2004. Preservation of bamboo structures. Ghana Journal of Forestry 15–16: 40–48.

- Seethalakshmi, K.K. & Muktesh Kumar, M.S., 1998. Bamboos of India: a compendium. Technical Report No 17. Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi, Kerala, India & International Network for Bamboo and Rattan (INBAR), Beijing, China. 342 pp.

Other references

- Barbosa, J.D., de Oliveira, C.M.C., Duarte, M.D., Riet-Correa, G., Peixoto, P.V. & Tokarnia, C.H., 2006. Poisoning of horses by bamboo, Bambusa vulgaris. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 26(9): 393–398.

- CAB International, 2005. Forestry Compendium. Bambusa vulgaris. [Internet] http://www.cabicompendium.org/fc/datasheet.asp?CCODE=BAM_VU. June 2007.

- Clayton, W.D., Davidse, G., Gould, F., Lazarides, M. & Soderstrom, T.R., 1994. Poaceae. In: Dassanayake, M.D. (Editor). A revised handbook to the flora of Ceylon. Vol. 8. Amerind Publishing Co., New Delhi, India. 458 pp.

- de Carvalho Jr, A.A., 2001. Primeira constataçâo do teleomorfo da ferrugem (Kweilingia divina) do bambu (Bambusa vulgaris) nas Americas. Summa Phytopathologica 27(2): 260–263.

- de la Mensbruge, G., 1968. Techniques de plantation et coût de production du bambou pour la fabrication de la pâte à papier. In: Pulp and paper development in Africa and the Near East. Vol. 2. FAO, Rome, Italy. pp. 715–729.

- Duriyaprapan, S. & Jansen, P.C.M., 1995. Bambusa bambos (L.) Voss. In: Dransfield, S. & Widjaja, E.A. (Editors). Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 7. Bamboos. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, Netherlands. pp. 56–60.

- Gurib-Fakim, A., Guého, J., Sewraj, M.D. & Dulloo, E., 1994. Plantes médicinales de l’île Rodrigues. Editions de l’Océan Indien, Rose-Hill, Mauritius. 580 pp.

- Igoli, J.O., Ogaji, O.G., Tor-Anyiin, T.A. & Igoli, N.P., 2005. Traditional medicine practice amongst the Igede people of Nigeria. Part 2. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 2(2): 134–152.

- Kalanda, K. & Bolamba, K., 1994. Contribution à la connaissance des plantes médicinales du Haut Zaïre. Les plantes utilisées contre les maladies de la peau à Kisangani. Revue de Médecines et Pharmacopées Africaines 8(2): 179–188.

- Khristova, P., Kordaschia, O., Patt, R. & Karar, I., 2006. Comparative alkaline pulping of two bamboo species from Sudan. Cellulose Chemistry and Technology 40(5): 325–334.

- Koshy, K.C. & Jee, G., 2001. Studies on the absence of seed set in Bambusa vulgaris. Current Science 81(4): 375–378.

- Latham, P., 2007. Plants visited by bees and other useful plants of Umalila, southern Tanzania. Third edition. P.Latham, DFID, United Kingdom. 216 pp.

- Mishra, S.C. & Thakur, M.L., 1998. Laboratory Evaluation of natural resistance of bamboos to termites. Indian Forester 124(12): 1043–1046.

- Ndiaye, A., Dialoo, M.S., Niang, D. & Gassama-Dia, Y.K., 2006. In vitro regeneration of adult trees of Bambusa vulgaris. African Journal of Biotechnology 5(13): 1245–1248.

- Papadopoulos, A.N., Hill, C.A.S., Gkaraveli, A., Ntalos, G.A. & Karastergiou, S.P., 2004. Bamboo chips (Bambusa vulgaris) as an alternative lignocellulosic raw material for particleboard manufacture. Holz als Roh- und Werkstoff 62: 36–39.

- Ramanayake, S.M.S.D., Meemadumaa, V.M. & Weerawardenea, T.E., 2006. In vitro shoot proliferation and enhancement of rooting for the large-scale propagation of yellow bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris ‘Striata’). Scientia Horticulturae 110(1): 109–113.

- Rugalema, G.H., Okting’ati, A. & Johnsen, F.H., 1994. The homegarden agroforestry system of Bukoba district, north-western Tanzania. 1. Farming system analysis. Agroforestry Systems 26(1): 53–64.

- Sarangthem, K., Singh, L.J. & Srivastava, R.C., 1998. Isolation of stigmasterol from fermented succulent bamboo shoots and its biotransformation into ADD using Arthrobacter globiformis. Indian Journal of Plant Physiology 3(4): 249–252.

- Sarpong, M.K., 2000. Evaluation of bamboo utilization in Kumasi. BSc thesis, Institute of Renewable Natural Resources, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, Ghana. 40 pp.

- van der Zon, A.P.M., 1992. Graminées du Cameroun. Volume 2, Flore. Wageningen Agricultural University Papers 92–1. Wageningen Agricultural University, Wageningen, Netherlands. 557 pp.

Sources of illustration

- Dransfield, S. & Widjaja, E.A., 1995. Bambusa vulgaris Schrader ex Wendland. In: Dransfield, S. & Widjaja, E.A. (Editors). Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 7. Bamboos. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, Netherlands. pp. 74–78.

Author(s)

- M. Brink, PROTA Network Office Europe, Wageningen University, P.O. Box 341, 6700 AH Wageningen, Netherlands

Correct citation of this article

Brink, M., 2008. Bambusa vulgaris Schrad. ex J.C.Wendl. In: Louppe, D., Oteng-Amoako, A.A. & Brink, M. (Editors). PROTA (Plant Resources of Tropical Africa / Ressources végétales de l’Afrique tropicale), Wageningen, Netherlands. Accessed 22 December 2024.

- See the Prota4U database.